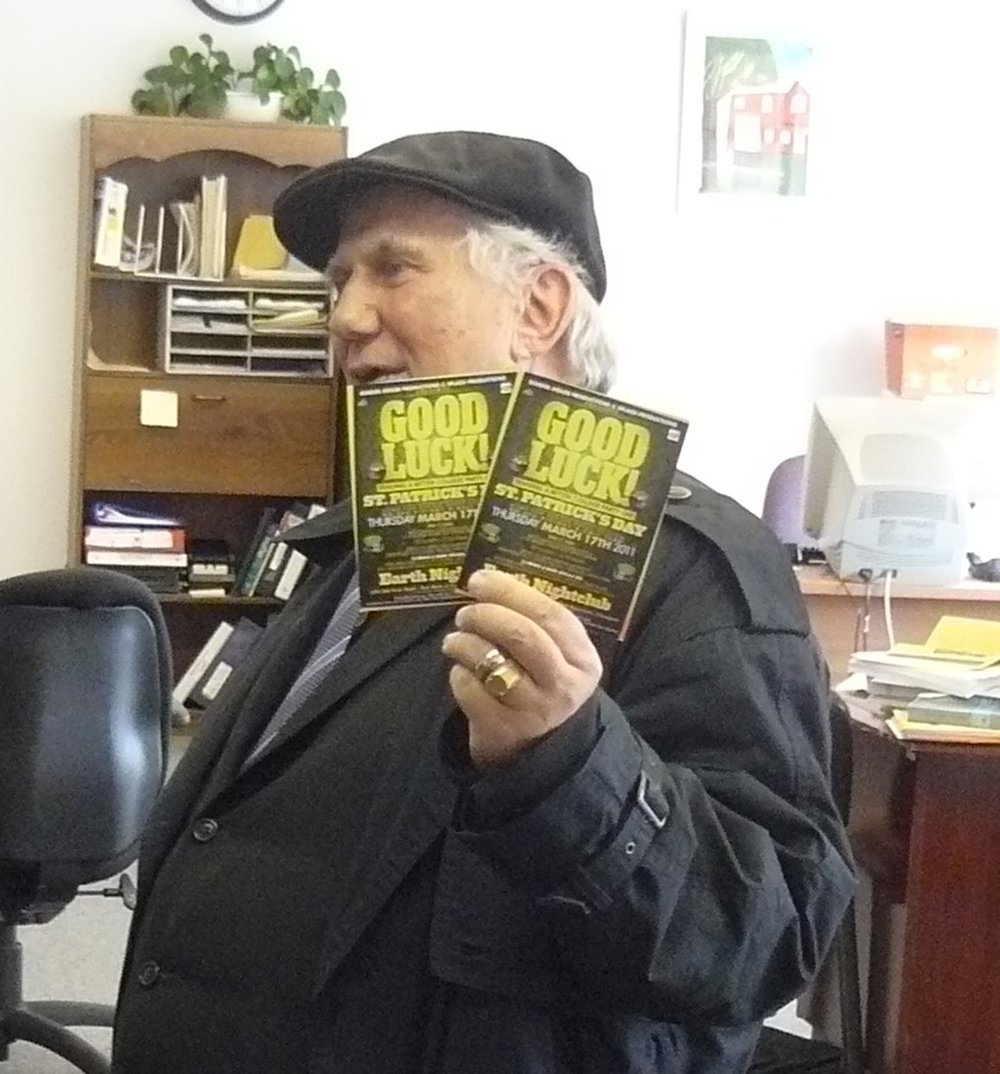

Chronicle Vendor Ray Jacobs

Adopted Roots of Goodness: A Profile of Tough

By Luke Drotar

Living in Ohio since the mid-80s, in one way or another, has muffled most of Raymond’s Bayou drawl. He is gregarious and wary. He will watch you laugh for a split second too long as if to make sure that your laugh is true, that you’ve gotten the joke. He makes sure. Raymond does everything he can to get his point across; his expression runs the gamut. He’ll yell across the room to bother a friend until he or she comes over to confirm a fact—Raymond’s side of the story—for him. He’ll look around the room to see if anyone’s watching while he whispers a detail through the corner of his mouth; a secret. He is smart, tactful.

Living in Ohio since the mid-80s, in one way or another, has muffled most of Raymond’s Bayou drawl. He is gregarious and wary. He will watch you laugh for a split second too long as if to make sure that your laugh is true, that you’ve gotten the joke. He makes sure. Raymond does everything he can to get his point across; his expression runs the gamut. He’ll yell across the room to bother a friend until he or she comes over to confirm a fact—Raymond’s side of the story—for him. He’ll look around the room to see if anyone’s watching while he whispers a detail through the corner of his mouth; a secret. He is smart, tactful.

It’s obvious that Raymond understands Ohioans, the way we are, our Midwestern expectation of politeness. His panhandling line, which he relates to me in two rapid-fire seconds, used to be: “Spare any change to help feed the homeless? God bless you. Have a good day. [And] Thank you [if you gave me a quarter].” He is a survivor, and he learned quickly that to both survive on the streets and stay out of prison he had to be honest and unaggressive in his panhandling because Clevelanders would ignore him to death if he acted otherwise.

“I think that most people look at you as you are. If you’ve got a good heart and you do the right thing, then they’re right there with you…I wasn’t running people down the street saying gimme gimme gimme…I did the right thing. I stood in one spot. I never left that spot. Reliable. Honest. If you dropped something…I found wallets with money in it. I took ‘em to the bank, turned them in. I found cell phones, turned them in. I found a $500 money order, turned it in. The guy came and claimed it and got his receipt. He gave me a reward. I didn’t say I didn’t get rewards. They didn’t have to give me anything though.”

His ethic of reliability and honesty put him in touch with the manager of a bank near East 9th & Euclid Ave. who Raymond noticed was watching him one day. “[The bank manager] said, ‘The way you do it, I wish they all did it. You’re not aggressive. Anything I can do for you I will do.’ He came out and gave me $10 dollars and said, ‘Will you be back tomorrow?’ If you let me here, I’ll be here. And then I was there for ten years at that spot. We grew old together…Bank security, everybody protected me there. I had three purse snatchers arrested before then. Think about it: I’m like extra eyes, extra ears out front.”

“How do you earn people’s trust? You do the right thing. He’d give me $10 and send me over to CVS. Get me this, get me that. He probably didn’t really need whatever it was. And I’d bring him his change. He’d give me a $20 one day to give to his son. I did it…It shows honesty, see. He gave me an envelope to take over to Huntington and I came back with what he told me to come back with. He never even looked to see if it was all there. One lady came out with a $100 bill, must’ve been a bank president or something. ‘I need you to go get a rain umbrella’ and I went over and got it and brought it back with her change and everything. She looked at me and said, ‘You are honest; he was right.’…All little tests.”

But as our conversation begins to drift from his experience first as panhandler and now as a street newspaper vendor to talk of the past and how he came to be in Ohio, the name of his hometown, New Orleans (“NuOwlin”), rolls off his tongue in a way that tells me that I’ve already forgotten that he hasn’t always lived here. Instead, he adopted Cleveland as a home (or vice versa) after being dropped off by a prison van at a gas station on Lorain Road in North Olmsted after twenty-six years behind bars, first in Angola (LSE) and then in the Ohio prison system. His comments on the experience are informed, no-nonsense: “I’m not saying that extradition shouldn’t be. But I think wherever they picked you up at they should be able to send you back to…If you’re not from Ohio, you shouldn’t be dumped in Ohio after your time’s up and left on the mean streets of Cleveland…It’s not made for you to make it. If you’re gonna make it, you’re gonna make it on your own.”

Raymond didn’t stay in shelters for very long during the mid-90s: “Too noisy. If I wanted to smell another man’s butt again I would’ve stayed in the penitentiary.” He instead slept under bridges and highway on-ramps, in sleeping bags and on cardboard.

Imagine, if only for a second, having nothing to your name except the clothes on your back and your state pay of twenty-four dollars. Raymond: “How far is 24 dollars gonna get you? A couple meals and a cup of coffee and guess what, you’re hitting the streets.”

As much as a part of our culture may relish the idea of no possessions, its reality is bothersome and rare. Raymond, however, despite being a thousand miles from his beloved New Orleans, with no way of getting home (no money) or of getting a job (criminal history), faced this stark reality unfazed. “I was free. That’s what it was. I could celebrate freedom. For 26 years I was incarcerated. I had no one telling me what time to go to bed, what time to get up, where I can go…the simple pleasure of being free.”

Raymond knows that his experience has been unique: “Not every one is Mr. Nice Guy out here…you come out, you have no job. And this is why you have a big return rate. They have nowhere to go. After a minute, they get tired of panhandling and the next thing you know it, you’re robbin’ someone on the streets.”

Raymond views the lack of services available for folks re-entering from prison as something more nefarious than the community just being short on funds: “It’s a trap…You and me want to see them stay out of the system, but the prison system wants them to come back in the system. It’s all about the money. The more people that keep a number or get a number, the more money goes into the system. Once the system starts losing money because they can’t get new offenders, then they’re in trouble.”

Raymond shared a story from his days as a panhandler about how we are always tested; about the merits of staying good even in the face of dangerous adversity:

“Back when the Flats was boomin’, a guy comes by. It was raining. I said, ‘Sir could you spare any change to help feed the homeless, I’d really appreciate it.’ He looked at me and started cussing like crazy and I said, ‘God bless ya, have a wonderful day.’ You know, my mind, aaah. [Ray gestures as if repulsed by the cussing] He came back; and he trapped me. He trapped me! I thought, Oh my God this guy is gonna kill me cuz he doesn’t like me. He said, ‘Did you just say God bless you?’ I said, ‘Yessir, I sure did.’ You know I can’t lie, right? He reached into his wallet and gave me a $100 bill. I said, ‘Thank you sir very much, God bless ya.’ He said, ‘Sheeeeeeya said it again buddy’ and gave me a $50, and I said it again and it just kept comin’, like it was natural. And he gave me another $100. So then I went up to what used to be the North Point Inn and got myself a room for the night. $250 dollars, I’m out of the rain, I’ve got a place to stay. Guess who’s checking in when I am? He said, ‘Give him a week’s rent on my credit card.’ Next morning he came to my room and said, ‘Ya ate breakfast yet?’ I said no. He said, ‘Well let’s go get it.’ So we went and got breakfast together. At breakfast he gave me an envelope with $750 in it. Plus the week’s rent. So see? Kindness, goodness, they pay. It was a good day.”

First published in the Cleveland Street Chronicle in 2011. Copyright NEOCH and the Street Chronicle